We got incredibly lucky. Ed and I almost got to the end of an error chain that could have very likely ended in his death. I apologize up front for starting with an austere tone, but we just learned some VERY important lessons that I am morally obligated to share with as many people as will listen. Given our backgrounds in aviation and his in engineering we should have known better than to make certain decisions that we did. We f*cked up, and we got lucky–plain and simple.

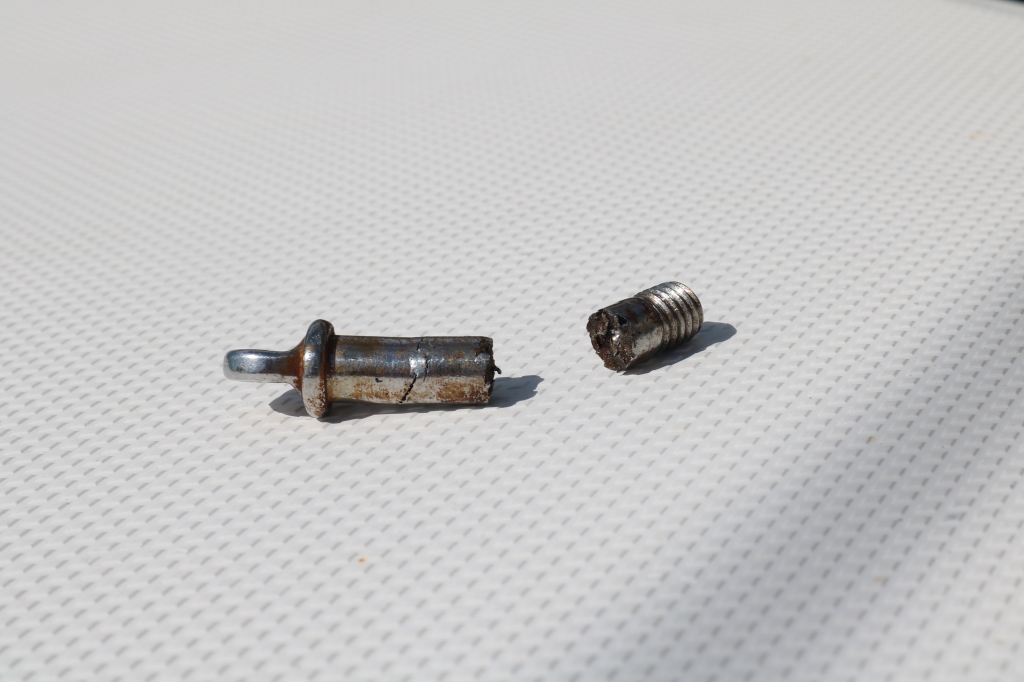

Pictured above is the shackle pin that attaches the head of the mainsail to the block that the halyard goes through to hoist the sail. The main halyard also does double duty as person-lifter when work must be done up the mast. I had hoisted Ed up the mast to try and troubleshoot an anchor light problem just minutes before the pin broke. We neglected to inspect its condition before using it when we had every reason in the world to have done so.

The title of this blog is a nod to a popular column in Flying magazine called “I Learned About Flying from That.” The column has long been a popular feature in Flying where pilots submit their stories of their lessons learned from poor decisions that almost ended catastrophically…the lucky ones. Unfortunately, many of those who are unlucky victims of the error chain never get to share their story. Some of the stories are truly amazing accounts of pilots narrowly escaping a giant pickle, some are more mundane, and some are “head-slappers” due to inexperience. Thankfully, aviation now has a culture where pilots (and other aviation professionals) are encouraged to share their mistakes and lessons learned. I have not yet encountered this same culture in sailing/boating, but I am also a newcomer to the activity. Perhaps it is because sailing is more forgiving of mistakes than flying? I don’t know.

In any accident there is almost never (maybe actually never) any singular event that goes wrong that creates the accident. There is always a series of failures, mistakes, or missed opportunities for correction that when linked together end in an accident. Sometimes plain, dumb luck is the last thing that saves you. Sometimes it’s a brilliant save by someone at the end. When we humans do it right, a systemic stop-gap breaks the error chain before it gets going too far.

Our error chain started almost two weeks ago with our sail from Black Point to Elizabeth Harbour (where we are currently located). It also started with something banal in the form of a couple of simple assumptions that led to a simple miscommunication. We had, essentially, two sailing legs on our last trip with a small section that had to be piloted under power in between. On our first leg, which was kind of on the short side, I thought that we might get away with making adequate speed sailing with the genoa only since the main sail can be a bit of a pain to deal with. We unfurled the genoa, but it became obvious that we were not going to make the cut we had to navigate through at slack tide at the speed we were going. We then proceeded to raise the main with one reef given the wind speed. Typically, if one is going to sail both main and genoa, the main goes up first for a few reasons which aren’t relevant to this discussion. That said, it’s not a terribly difficult process to do it backwards provided the sea is calm…which it was.

My inexperience inserted the first mistakes into our error chain, and also an assumption on Ed’s part that I had a particular piece of knowledge that he really didn’t have very good reason to assume I had. When we raise or lower sails, I am nearly always at the helm, and Ed takes care of any lines that need handling that are not at the helm. As we now have an electric winch, and most lines run back to the helm, this means I actually take care of most of the mainsail tasks. Ed works as my second set of eyes at the front, takes care of clipping the cringles when we reef, and any other stuff that comes up from time to time. Steering and handling the halyard and reefing lines can sometimes feel like I am a three-legged cat in a poo burying contest. As I am still learning, this activity can be a bit task-saturating for me which leads to stress. Stress, in turn, can lead to tunnel vision. The wind noise and noise from the winch also makes verbal communication difficult. Because of this, Ed uses hand signals to communicate certain instructions. Some of the signals he uses he borrowed from his work in construction from his younger years. Before that sail, we had never actually sat down and discussed our set of hand signals. I was just sort of picking them up on the fly and through context. This is a dynamic that is ripe for expectation bias to enter the picture. I knew better because of my career in aviation, and I should have insisted that we standardize and discuss our hand signal usage.

When we raised the mainsail this time, it was also the first time we had hoisted the main directly into a reefed configuration with our new line set-up (we just had them changed before leaving Florida). I got us pointed into the wind, set the clutches on the reef lines as needed, and then started to raise the main on the electric winch. Ed uses a hand signal where he points his index finger up and moves his hand in a circle to indicate that I need to winch the halyard up. When he stops, I stop winching so he can do whatever he needs to do in the moment. When everything is in position I get a thumbs up, and then I steer us off the wind and back on course while he tidies up some line up front. This time, I went a little too far on the halyard and he inverted his signal by pointing down and moving his hand in a circle. It was the first time he had given me the signal, and because I didn’t know to look for it, all I saw was a fist spinning and in my world that meant winch the halyard up.

As I kept winching, I could hear the motor working much harder, but as I was seeing Ed’s signal to keep going (or so I thought) I deferred to his experience. My task-saturated brain defaulted to “follow directions” at the expense of other inputs that I would ordinarily know meant I needed to take a different course of action. Ed finally yelled at the top of his lungs to let out the halyard which I did immediately. The damage was done though, unbeknownst to us at the time. The rest of our trip went off without a hitch. I piloted the cut well even though the current and waves were…ahem…sporty, and we got the sails back up for leg number two with no problems. We arrived into Elizabeth Harbour, dropped the anchor, and then proceeded with other stuff we needed to do. It was at this point Ed discovered we had bent one of the halyard fairleads. My over-winching had caused damage on a part that ordinarily can take a lot of load. Ed was obviously also worried about the sheave at the top of the mast being bent and other potential damage.

We got a hold of a sail guy (for lack of a better term) when Monday came, explained what had happened, and sent lots of pictures. We received assurances that it was unlikely the fairlead would fail (provided we don’t over-winch it), and even if it did, we would still be able to handle the sail by using the winch on the mast. The sheave at the top also looked fine from below, and we figured we’d give it a better look next time work had to be done up the mast. Thankful that we wouldn’t have to worry about fixing the damage until our return to the states, we put the whole mess behind us for now thinking we had dodged a bullet by not doing worse damage.

The day to do work up the mast came today. Our anchor light (which is at the top of the mast) has been working intermittently since we bought the boat. After talking over how it behaves with some folks, we landed on the conclusion that a loose wire at the bulb was the probable culprit. Ed gathered up the tools he needed, got himself in the bosun’s chair, I gave a good look over that everything was connected and strapped properly, and hoisted him up the mast. Upon reaching the top, he realized that he couldn’t get high enough to see on top of the mast, let alone try to fix it, so I lowered him down, and we discussed how we might remedy that problem. After 20 or so minutes of brainstorming, I suggested that we rig up a strap to the chair that would allow him to put his foot into it like a step and allow him to sort of stand up on the halyard. He unscrewed the shackle to hook up the bosun’s chair again and the pin broke right in his hand. My eyes got as big as dinner plates and I probably turned a bit paler. Had that pin failed any earlier or any later Ed could have fallen. Our mast is 71 feet. Injury would be likely, and death possible depending on how far up he was.

The shackle that was on the block was a bit on the older side and might have had some metal fatigue. Without a microscope there is no way to know for sure. It also might have already been bent a little from use; Ed recalls that the pin screwed in and out with difficulty. We no doubt exacerbated the problem when I over-winched the halyard. Neither of us even thought to inspect it. We had bent a brand new fairlead, and we didn’t think to inspect a block and a shackle that were older. Yeah…stupid. I am shaking my head at myself as I type at how dumb it sounds. Even dumber that we trusted it to hold a human. I feel both ashamed that I missed it and thankful it didn’t end badly.

Lessons Learned

I once received very good advice when I was a young aviator:

Everyone starts out with two bags. You start with a full bag of luck and an empty bag of experience. The trick is to fill your bag with experience before you empty your bag of luck.

I think this advice applies to all facets of life. We emptied our bag of luck a little bit today. I think we also filled our experience bag some too.

Things I learned through this experience:

- The electric winch motor is the strongest component. It will keep running even if it pulls itself off of its bolts. I think this is an unsafe design and will be exploring options to depower the motor so we cannot mechanically repeat the over-winching mistake.

- Hand signals are useful in a noisy environment, but are limited in what they can communicate…especially when the “speaker” and “listener” do not have a common hand signal language. If there is ANY doubt that all involved are 100% up to speed on what signals will be used and what they mean, brief it first.

- Headsets. Get them. Use them. They are also colloquially known as marriage savers. We were given this advice before we got the boat; we figured we’d get around to it when it was convenient. If I had it to do over again I would buy the headsets BEFORE the boat.

- If you bent or damaged one item that line runs through, check every single other piece of anything that the line was in contact with when the damage occurred. The obviously bent part may not actually be the weak link.

- Be thankful for every day you get and take care of each other!

I’m sure there some other lessons we should have learned here. Please leave them in the comments below! We are humbled by this experience, and grateful it didn’t end badly.

Two observations both learned from time spent with Brion Toss. Always tie your halyards to the bosons chair with a bowline, never use a shackle and always use two lines. We hoist on the spinnaker halyard and back up with the topping lift.

Enjoy your 8 am moderating and hope we have a chance to chat. I spent 40 years as a professional pilot.

Ed and Carol on SV Dolphin

LikeLike

Sound advice.

LikeLike

Great article! With your permission, I would like to refer to parts of it when I am writing and teaching in order to provide an additional example that is more directly relatable to a certain group of students when teaching the “accident chain” and other lessons.

I consider luck to be that place where preparation meets opportunity. Your use of the phrase “dumb luck” (as opposed to “good luck”) is useful to reinforce my insistence that any students that I agree to teach commit to a thorough study of the materials (preparation) that I assign, as well as those they discover during the course of their studies.

I love the “two bags” advice! I am going to modify it as follows to encourage deep study by students at all levels, including CFI candidates, in order to develop “good luck”:

Everyone starts out with two bags. You start with a full bag of luck and an empty bag of experience and KNOWLEDGE. The trick is to fill your bag with experience and knowledge before you empty your bag of luck.

Cheers, Phil

LikeLike

Oy! How about coming back to Portland some day in one piece. 😉

LikeLike

Isn’t yachting GRAND!

LikeLike

If you are thinking about stepping out of your chair to get to the Top plate of your mast to inspect or repair anything your pretty brave or something I won’t mention. One may wanna think about adding 2 to 3 foldable mast steps positioned just so,,, below the mast head so that you may get the lift you need to work on mast head gear while aloft. One would also require a climbing harness bosun chair in lieu of a comfy rigid bottom bosun chair. Once aloft and up on the steps be sure to tie an additional safety line into any bale one can find at the mast head for an extra measure of safety. So you are attached,,, tied too(never shackle) a halyard or two and the short safety line installed once in position. It’s a ballsy maneuver best suited for thrill seekers,,, or cheap bahstaads that don’t want to pull their rigs every time there’s a problem with mast head gear. I’m both and have done it many times. Good luck and have fun .

LikeLike

Sounds shocking and distressing. So glad you are both okay! Hope there will be no more near misses on your adventure of a lifetime. Stay safe and happy travels 🙃😘

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Another valuable tip. Wear the head gear,,, but use hand signals. Head gear can mall function or fall off ones head. Having hand signals and/or understanding sight reading is so valuable. You can use it everywhere, for many diff situations. 👍🤌👉👈👎👌🤚🙏🖕✌️👆👇SAY NO MORE,,, literally. My GF and I ran a boatyard for years. She was the crane operator. I was the ground guy. We NEVER EVER spoke during an event. Equipment was too loud. Never had an accident and always used hand signals. Even today (retired) we use hand signals at the grocer, restaurant, gas station, church, family reunions etc… YA MON

LikeLike

Glad that shackle came in two when it did… My adventures up the mast via a 4 to one block and tackle arrangement were similar in some respects. About the fourth time up I had something arranged that allowed me to reach and replace the bulb. Was anyone watching as I did unplanned high wire gymnastics for a while in a less than ideal contest between gravity and my strength / flexibility. The foot stirrup worked until I tried to sit back down…

LikeLike

Wow! And glad you are safe. Great writing too!

LikeLike